Intro

God knows the Internet doesn’t need another essay on Prometheus, but I’ve been on a bit of a bender recently and I’d like to write my thoughts down. Prometheus scratches the Literature itch that poems and novels sometimes do, the kind I’d debate for college classes in the form of ten-page essays. I find such textual based arguments enjoyable, though I do acknowledge that I’m by no means the societal norm.

Before I start waxing poetic about the movie, I want to talk about the original script. Before Damen Lindelof and Ridley Scott made the changes they did, Jon Spaihts wrote a direct Alien prequel. The movie featured facehuggers, a version of David a bit more cold-hearted and evil than the one we got, and Xenomorphs aplenty. It was the movie fans wanted, though it wasn’t the movie Ridley Scott ever promised we’d get. The Engineer died at the end and left a handful of Xenomorphs to kill everyone, and Shaw had to survive, much like Ripley did in Alien and Aliens.

I’m glad we did not get that movie.

Such a movie would have been great, don’t get me wrong, but the horror delivered in that movie would have completely replaced or overshadowed the questions and the point of Prometheus. We’d have gotten a horror movie—and I’d have loved it I’m sure—and not the film Prometheus turned out to be.

Since there are so many things to talk about, I’m just going to section this essay off. It’s simply easier, and honestly, I don’t know where I might go in terms of discussion.

The sections are: The Engineers and Xenomorph Comparisons, Did the Engineers Create the Xenomorphs, The Black Goo, Why the Engineers Changed their Minds, and an Outro

The Engineers and Xenomroph Comparisons

Before I can even begin talking about the movie, I need to discuss the Engineers and the Xenomorphs.

But before I talk about either of them, I should talk about the story of Prometheus. Prometheus is the Greek Titan who created humanity. He sculpted us out of clay, and at a point in our primitive culture, he gave us the gift of fire. He went against the Greek pantheon to develop us and give us intelligence, much like Satan went against God to give Adam and Eve the gift of knowledge. Bestowing fire (knowledge) upon mankind was frowned upon, and so Zeus captured and chained Prometheus to a rock where every day an eagle would eat his liver.

The story of Prometheus is important for a few reasons, the most obvious being that the Engineers created humans much like the Greek Titan did. The ancient carvings show that the Engineers continued to come to earth and bestow knowledge of themselves to the primitive humans. The common trope of such science fiction is that the advanced aliens helped humans develop in forms of civilization and culture, much like how Prometheus gave the fledgling humans the knowledge of fire. But, the idea of sacrifice is present throughout both kinds of myth, both Greek and film inspired. Prometheus was chained to a rock to forever be tormented by a hungry Eagle, and in order for the Engineers to create life, one must first die.

The Engineers themselves are a kind of perfect being. To be sure, they look scary, falling so far into the uncanny valley that I’ve had nightmares about them, but they hold a kind of perfection in their form. They are white (this is thematically important and has nothing to do with race), they are muscular, they are hairless, and they are tall. They do not slouch, they are powerful, and they are intelligent. They resemble a kind of Olympian hero.

That the Engineers consider themselves Gods is a simple fact. The frightening face carved into the top of their temple resembles not a deity or a chimera, but an Engineer. The giant stone face in the ampoule room is that of an Engineer. The murals on the walls of the ampoule room feature Engineers. The corridor leading from the temple to the underground ship plays host to statues of Engineers.

In short: the Engineers worship themselves.

We can’t really blame them for this. Look at their accomplishments. They’ve seeded a universe with life that will eventually grow sapient; they’ve created technologies that dwarf human invention in this futuristic scifi world. They literally are Gods with a capital G.

But they respect the sacrifice and the price it takes to create. If we look at the Engineer in the opening scenes of the movie, he is giving himself up in a ceremonial fashion. He jettisons his robe and kneels down to open the vial containing a black substance that will destroy him. He solemnly drinks it of is own free will as a spaceship flies away. In the extended version of this scene, other Engineers are gathered around him to watch, and the whole ordeal resembles a religious ceremony.

As David says, “big things have humble beginnings.” One Engineer for a race of creatures. For a race of humans.

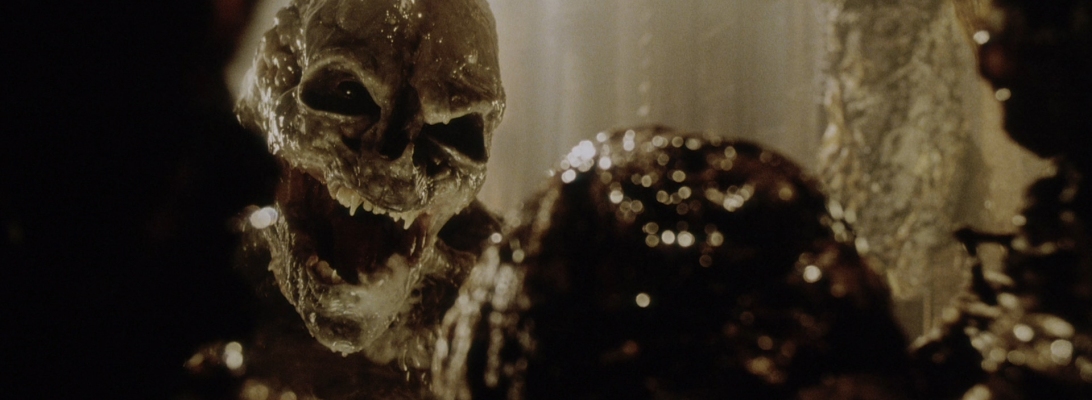

The Xenomorphs are the antitheses of the Engineers. If the Engineers are Gods, then the Xenomorphs are a race of Satans bent on destruction. In terms of appearance, the Engineers are the Olympian hero while the Xenomorphs are monsters of our worst nightmares. They realistically resemble nothing earthlike, being jet black in color, possessing large arching skulls, two sets of jaws, six fingers, and every other attribute fans of the Alien series are familiar with. The Engineers hold the pinnacle of creation and intelligence; the Xenomorphs operate under extreme instinct and base needs. Physically, they are opposites.

And they differ on a philosophical level. The Engineers must sacrifice themselves to create life; The Xenomorph must sacrifice an other to create life.

In religious myth, this would pit them against each other. The Engineers would be the ambivalent gods sacrificing to create and spread knowledge and the Xenomorphs would be scary devils destroying everything in their wake. Yet this is not the case. The Engineers themselves are by no means ambivalent as we see in the film, and the Xenomorphs are too chaotic and primal to be evil. They simply are what they are.

Let us go to the murals and statues located in the Engineer pyramid. The first mural we see is this:

a picture that should remind everyone of a famous painting.

There are two things to note here. First, the Engineers worship themselves as seen in other artwork. The fact that this painting exists means they are also worshiping something involving the Xenomorph. There are two ways to look at that. First1, the Xenomorph is a creature they found, something just as perfect as themselves yet opposite and therefore something to be worshiped. Second1, they created the Xenomorph as perfect and are worshiping something they made. Both arguments seem plausible. Second, the difference in paintings is quite obvious. In the first painting, the Engineer is subjugating the Xenomorph while the Fresco painting shows equality between God and Adam.

The difference is in motive.

The entire ampoule room is set up as a kind of alter room for the Engineer’s ego. The center piece is a sculpture of one of their heads, the walls are filled with paintings—some involving them—and the floor is evenly spaced with ampoules of black goo, their highest creation. There are ampoules aplenty in the cargo areas, yet this room holds them in perfect formation.

As we see later on in the movie, the black goo held in these ampoules does something quite different than the black goo of the first ceremonial scene. This second black goo is a kind of mutagen, and it creates the kind of destruction we expect from the Xenomorph. The first mural we see is that of the Engineer subjugating the Xenomorph, and since the black goo is as destructive as the Xenomorph, then the entire room must be the glorification of the Engineer’s capability of harnessing the Xenomorph’s destructive power. The Engineers have manufactured and controlled the chaotic destruction of the Xenomorph, and this is their highest achievement, not that of creating man.

If man were their highest achievement, we’d have seen murals of mankind interacting with Engineers. Instead we get the opposite, manmade carvings and cave paintings of humans worshiping the godlike Engineers.

But, the Engineers were unable to actually control the Xenomorphs as we learn. There is a spill of some kind, and the humans show up thousands of years later with all of the Engineers dead and mummified. Even the lower creation, the humans, wind up foiling the Engineer’s godlike plans. Janek crashes his ship into the Engineer craft and Shaw causes the Engineer’s death. Prometheus gave mankind the gift of fire and knowledge, yet after a few thousand years, we no longer believe Prometheus was ever real. He was simply a myth created by a folk looking for answers where they could find none.

Creations have a mysterious way of getting away from their creators and destroying everything. Such is the way of things.

Did the Engineers Create the Xenomorphs

This is a question that has been around since Alien. The Derelict contained an entire nest of Xenomorph eggs and one lone pilot who died because of them. We don’t know the pilot’s intent, but it is later said that the beacon that drew the Nostromo was a warning and not an S.O.S. Either way, the Xenomorph is described as the “perfect killing machine,” and through Geigeresque stylization, looks to be a mix of biological and mechanical parts.

However, my answer to this question is “no.”

First, let’s look at the Xenomorph. Though the creature is descried as “perfect,” and though it is featured in Engineer murals, it logically isn’t perfect. Its lifecycle is drawn out and cumbersome, and during three stages of its life (if we count the egg) the creature is highly vulnerable. Though a walking biological weapon the facehugger might be, it as a creature holds no offensive capabilities other than jumping and infecting. It cannot infect from long range, it isn’t very big, and its only means of defense—acidic blood—comes from being attacked. It must hide, wait, and then attack, and after it attacks, it must hope that it isn’t spotted before implanting an egg. The chestburster phase has even less defense, being but a small snake with sharp teeth. It’s not until the fourth phase that the Xenomroph comes into its destructive power.

And really, a creature that starts off as an egg only to birth another kind of egg with legs is wholly redundant.

Perfection is highly subjective, but the Xenomorph is not perfect. The Engineer himself isn’t perfect either, being very much mortal. But the idea of perfection isn’t about the physicality of these creatures. The Engineer’s philosophical view involves creation and sacrifice, and both he and the Xenomorph do this, but in different ways. The Engineer must die to create while the Xenomorph must kill to create, so to the Engineer, the Xenomorph’s form of creation is perfect.

The murals on the walls of the ampoule room are the only clues we get about the Engineer’s relationship with the Xenomorph, but I think the clues are enough to yield an adequate answer.

We’ve already looked at the first mural.

The second mural is this one:

the third is this one:

The second mural was only glimpsed at, but it was included in a Prometheus artbook. It is, clearly, an egg. The hands holding the egg appear to be that of a Xenomorph, though they are missing some fingers. The Xenomrophs in the Aliens movies feature six fingers while that one holds only four.

The third mural is that of a Xenomorph, though it also looks a bit different from the ones we saw in Alien and its subsequent sequels.

This all goes back to previously stated information. The Engineers worship themselves as seen by the artwork in the pyramid, and this ampoule room must be very important given the volume of artwork present and the evenly-spaced vials of black goo. The entire room is a glorification of a kind of achievement, and going by the first mural of the Engineer holding down a Xenomorph head, that achievement is controlling and dominating a chaotic race.

The Engineers are creators, yet we see no artwork of any of their other creations in this religiously-inspired room. There are no humans or other alien races, because at this point in their history, creating life and seeding planets aren’t achievements: they are simply things that the Engineers can do.

But taking a race of creatures that are the complete antithesis of themselves and finding a way to bend and control them? That is an achievement. There is no logic in creating a philosophical opposite to yourself that you cannot easily control, subjugating that creation, and then glorifying that achievement. The Engineers have rather large egos, but they can’t be blamed for that given the scientific wonders they have accomplished; however, I don’t think their egos are so big as to glorify what would be a fake accomplishment. There’s simply no point. It’s really only plausible that they found the Xenomorphs and bent them to their will in some fashion. That’s at least worth a mural.

The fact that the mural Xenomorphs look different from what we are used to seeing is also significant. If the Engineers can create life, then surely they can alter and mutate existing life, and the black goo in the ampoules does just that. We don’t know what the true Xenomorph looks like, be it that in Alien with its six fingers and tail, or that in the murals located in the ampoule room. What we do know is that the Engineers found them, conquered them, and that they can mutate existing life. So, either the murals depict the original Xenomorph being subjugated by Engineer science, or the murals depict what the Engineer created and controlled based off of the original Xenomorph.

There’s plausibility in both answers.

The thing is, the answer isn’t important. One of the major themes throughout the Alien movies is the inability to control the Xenomorphs. Always the Weyland Corporation wants a sample for their own nefarious needs, and always this backfires, creating an outbreak and widespread death. This continues in Prometheus. The Engineers thought they were able to conquer the Xenomorph, even had artwork depicting their achievements and prowess of this, but in the end, they failed. There was an outbreak—as there always is—and the Xenomorphs, in whichever form the mutagen altered them, escaped and killed everyone.

You can find chaos, you can alter chaos, and you can try to control chaos, but in the end, chaos will always revert back to its original, primal instincts. That is the Xenomorph, regardless of form.

The Black Goo

The black goo is both an amazing plot device and an amazing substance within the movie. It’s seen interacting six times, and each time it does something slightly different. Yet, I believe it has a consistency.

The black goo is a mutagen, as explained in the commentary, and I believe its function is that of liquid Xenomorph. Carrying actual Xenomorphs would be cumbersome and dangerous, and carrying a cargo of unhatched eggs is equally dangerous as seen on the Derelict in Alien. But, liquefying the pure chaotic essence of the Xenomorph and carrying it in vials is less cumbersome and not as dangerous, though still dangerous as we see in the movie.

Plus, finding a way to liquefy the Xenomorph essence is worthy of murals and self praise, which is the purpose of the ampoule room.

The first instance of black goo is in the very beginning. An Engineer drinks it, dies, and seeds life on Earth. I believe this black goo to be a different substance than what we see later in the movie. First, it acts completely different than the other black goo we see; second, the black goo in the ampoule room plays devotion to the Xenomorphs and Engineers, not humans or the spreading of life throughout the universe.

The second instance is the dead Engineer head. The characters bring it back to the ship and comment that it has some kind of organic substance growing out of it. When we look at the ghostly footage of the Engineers, this one was chasing the others and eventually fell over, its head then getting cut off. When the head is activated with some kind of electric substance, it sends the black goo into overdrive and causes the head to explode. Whatever the goo was going to do, it clearly wasn’t good or stoppable, as seen by the fleeing Engineers in the recorded footage.

The third instance is the black goo infecting some worms found within the pyramid. They turn into these snakelike, reptilian creatures with the ability to infect. They act like primitive facehuggers, even possessing the acid blood we expect from Xenomorph relatives. One wraps around Milburn’s arm (a homage to the facehugger wrapping its tail around a victim’s neck) and then dives down his throat to suffocate and impregnate him. Much later in the film, a wormlike creature (a kind of chestburster) flies out of Milburn’s dead mouth and slithers away.

The fourth instance is Charlie’s ingestion of a single drop of this liquid in an alcoholic beverage. We never see what will happen to Charlie, but I don’t believe he was going the route of the Engineer in the beginning of the movie. While the Engineer in the beginning drank a cup and Charlie only a drop, the difference in their weight, height, and muscle mass should have equated the two doses to a more equal amount.

That, and when Charlie looked into the mirror he saw a wormlike creature burrowing out of the bottom of his eyeball.

Worms are small and not complex when compared to humans. The worm simply mutated, having swum around in the black substance. But to be ingested by a large and complicated organism, the black goo would surely have a different, yet similar effect. Charlie was beginning to fall apart and crack, and I can’t help but wonder if he was slowly creating facehugger-type creatures within himself, acting as an egg. He was generating some kind of foreign substance, as seen by the worm in his eyeball.

The fifth instance is Shaw’s pregnancy. The black goo infected Charlie, creating some kind of foreign wormlike substance, and he sent that into Shaw when they had sex. Shaw’s baby grows quickly, similar to the rapid growth of a chestburster, and eventually acts like its own kind of facehugger later in the film. Like Charlie, Shaw becomes a kind of egg, generating a foreign substance.

The sixth instance is Fifield’s monstrous transformation, and this is the hardest to put down. In an alternate take of his antagonistic scene, he looks more akin to a Xenomorph, with a head that arches backwards and a skin much blacker in color. This can be found here. However, that isn’t what we get in the movie so it isn’t canon, though this alternate version makes much more sense to me and to the black goo as a whole.

Fifield’s infection is slightly different as it’s immediately introduced upon his death and mediated through his helmet. While it doesn’t turn him into a Xenomorph or a kind of reproducer of them, it does give him some characteristics of them. He becomes chaotic, violent, and very hard to kill. His mutation recalls images of the infected Engineer chasing down his companions before collapsing and having his head lopped off. That Engineer didn’t appear very Xenomorphic either, but his demeanor was that of Fifield’s: chaotic and violent.

What would have happened to Fifield and that infected Engineer remains a mystery as they are prematurely killed. But, given the imagery in the ampoule room and the characteristics of the other black goo infections, we can easily assume that these two infections would have lead to something Xenomorphic in nature.

Why the Engineers Changed their Minds

The Engineers created humans, yet the final climax and reveal of Prometheus is that the Engineers want to destroy their creations. They built us, they helped us grow as a society, and then they abandoned us only to want to come back and remove us from our home. Shaw desperately asks why as David is talking to the last Engineer on LV 223, but her question is never answered.

Damen Lindelof and Ridley Scott purposefully left the answer to this vague. Lindelof’s reasoning is that this ending prompts more discussion and publicity for the movie, and this is surely the case since people are still discussing it long after its release. But, he also believes that leaving the answer vague is better, since no answer is more mysterious and scary than an answer.

I believe him.

Look back at Alien and the Space Jockey. Even after rewatching that movie over and over, the Space Jockey remained scary because of his mysterious nature. What is he? Why is he on a ship filled with Xenomorph eggs? Where was he going with this cargo? How is he stuck to this chair? What does the chair do? Where is the Xenomorph that blew out of him thousands of years ago? The mystery was the best part of him, and there was an outcry from fans when they found out Prometheus would be about the Space Jockey. Such a movie would ruin the mystery that had been present for the past 30 odd years. Whatever Ridley Scott delivered, it wouldn’t be as good as what fans came up with and debated.

The mystery is what made the Space Jockey scary.

This same conundrum can be said about the Engineers and Earth. They changed their minds, and we aren’t to know why because any answer given would be unfulfilling. The movie is bad because there is no concrete resolution to this most important question versus this movie is bad because the Engineer’s motive for destroying the Earth is silly and nonsensical. The former is preferred over the latter.

If you watch the deleted scenes, David originally had a lengthy conversation with the Engineer regarding Weyland and eternal life. The conversation is interesting, but it strips away the power and mystery of the Engineer. It kills everything the movie did to establish the character. The conversation turns a godlike creature into another alien in a universe filled with them.

But, David puts it best when he asks Shaw if it even matters. To his android brain built upon logic, it doesn’t matter. The Engineers made us, they were unhappy in some capacity, and they want to try something new. An answer wouldn’t change their minds; it would only give us some useless reasoning before we all died. Blind luck saved the human race, not a plea for redemption. That’s what matters.

Shaw operates under the impression that the Engineers seeded Earth with life for a reasonable reason. Charlie feels the same way. When David asks Charlie why he was made, Charlie responds, “because we could.” David then remarks about being disappointed, and Charlie ignores the comment, not fathoming the idea that the Engineers created life on Earth simply because they could. By all accounts, we assume the Engineers had a good reason for seeding Earth because one must die, but we only know the smallest fraction of their culture and nothing about the way they think or view the universe. To them, Earth could simply be an experiment, and the black goo is a prime variable.

For a movie about searching for God, the characters hold a religious faith that the Engineers have some kind of purpose behind their plans. Charlie is an atheist in the movie, so his quest for a scientific creator replaces the religious quest for a God. But, he holds more faith than Shaw who is religious as seen by the cross she wears around her neck, a cross she never gives up despite evidence that God did not create mankind and therefore Jesus isn’t a mortal deity. Charlie is the first character to take his helmet off, putting faith in ancient technology. When he finds all of the Engineers dead, he’s completely crestfallen. Shaw looks to keep progressing as their team found the biggest scientific discovery imaginable, but Charlie can’t get past the fact that his faith in these aliens was completely destroyed. He acts like a religious follower who just found out God doesn’t exist.

Both operate under the guise that these star maps were invitations and not simply accurate star maps. Knowing nothing of this race, they assume the Engineers are friendly and want visitors, despite the fact that the Engineers have interstellar travel and can visit Earth anytime they want. They have faith in an ambivalent creator and not an apathetic experimenter, which is what the Engineers seem to be. The two presume answers for questions no one else asks, perhaps questions better left unasked. Do we realistically want to know who created us and why? What happens when that answer isn’t what we wish it to be? In Prometheus, everyone dies. I cannot fathom what society would do if this question was answered, but the outcome would be both grand and terrible.

Ignorance is bliss.

That is, I think the point of the movie. The question isn’t answered because the answer both doesn’t matter and shouldn’t be sought. However, that doesn’t mean there isn’t an answer hidden within the movie.

Let us once again return to the first mural:

If you look closely, you’ll notice two things. In the lower right corner is a picture of a facehugger. The entire Xenomorph lifecycle is depicted in the ampoule room, worshiped for itself and for its subjugation. In the lower left corner is a bipedal figure being facehugged. It’s unclear if this bipedal figure is a human or an Engineer, but given the ego of the Engineer and what this room represents, I think it’s that of a human.

The Engineers went around and seeded the universe with life for whatever purpose suited them. Then, they found the Xenomorphs, creatures that need hosts to reproduce, the perfect antithesis to creation, one who doesn’t need to sacrifice itself to create life. They found a way to control these creatures, make them their own. The only thing left to do is allow them to reproduce and fill the universe, creating a universe with the perfect creatures of light and the perfect creatures of darkness. Humanity did nothing wrong, we just weren’t perfect. The Engineers are Gods, the Xenomorphs are antiGods, and us lowly humans are apes.

The Engineers continued to show up on Earth and watch us and presumably guide us and bestow knowledge as per the Titan Prometheus. But, humans hold a different philosophy to creation than the Engineers. We don’t bodily sacrifice to create. We don’t hold life in such a sacred fashion as the Engineers do, and that must make us look like blasphemers.

Look at David. He was created by Weyland because Weyland wanted a son, and to see if he could create an android. Weyland created David for reasons of power and greed, and he is very much still alive. In a deleted scene, he considers himself a God and on the same level as these Engineers, but what does he know of sacrifice? He lives, yet he’s afraid of death and seeks eternal life on the guise that he deserves it for his abilities. The Engineer philosophy of creation cries at such blasphemy! It’s no wonder the Engineers wanted to use our self-absorbed planet as host to a more perfect and chaotic race, a race of creatures who understand the need for sacrifice.

David states it best, “Sometimes in order to create, one must first destroy.” Only to the Engineers and Xenomorphs, the qualifier isn’t “sometimes” but “always.”

That is, I think, the answer to this purposefully-unanswered question.

Outro

There are so many other things worth discussing in this film, but I’ve gone on long enough. I could write another handful of pages on the religious imagery alone in the film, the parallels between characters, and the general cinematography. There are simply so many things to look at and ponder (did you notice that after Shaw gives “birth” to the squid monster, she goes back and does exactly what Charlie does in front of that mirror, only in the opposite direction? (did you notice that the ships sent out to seed life are completed circles while the ships sent out to destroy are broken circles?)).

I absolutely love this movie.

I could go on, but I’ll end here.