Developer: Boss Key

Publisher: Nexon

Release Date: August 8, 2017

Platforms: PC (reviewed), PS4

Me and arena shooters go back to 2001 with Aliens vs Predator 2. That was the game that seduced me to the genre, to the exhilarating fragfest of twitch aiming and explosions—and Xenomorph pouncing. After that came Unreal Tournament: 2004 and then Team Fortress 2, but by then, I was starting to play a wider variety of games on a wider variety of systems. This lead to a gradual falling out with the genre as playerbases dwindled alongside my free time.

Those good memories never left though, and I’ve been on this lazy hunt for another arena shooter in the same vein of AvP2 and UT2k4 for what feels like a long time. TF2 is great, but it doesn’t have the speed I want.

Cue Boss Key’s Lawbreakers hitting the scene in 2017. My search is over.

In a way, Lawbreakers is a combination of two of the aforementioned arena shooters. It has the class system of TF2 mixed with the massive gunplay and wild speed of UT2k4. It’s just as addictive as both.

Yet the game isn’t a simple A + B = C. Lawbreakers throws enough twists and turns at the genre to stand on its own and succeed at everything it tries to do. It’s the best of old-school mechanics with all the shiny polish of 2017.

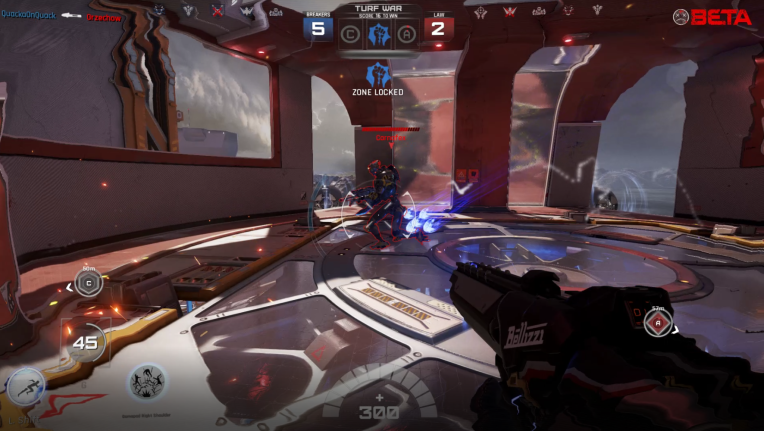

The biggest twist is the zero-gravity bubbles that reside in the middle of every map. Lawbreakers demands its audience go vertical when fighting, and that means getting off the ground and into the air. It makes for a strong learning curve, but once it clicks it feels absolutely amazing. It helps that most characters have their own ways to zip around the map, either through actual flight or things like grappling hooks and teleportation.

Lawbreakers is its own animal when it comes to combat, because attacks can come from any direction.

The game is class based, featuring a cast of nine characters to play, each coming with two special moves and an ultimate on a timer. There’s a lot of personality to each of them, though not quite as much as TF2 or Overwatch. Still, the little things help set them apart, such as the Battle Medic barking, “Here comes health!” or Juggernaut going, “Remember when I told you I’d kill you last? I lied!” I’m quite fond of most of them.

Before we continue, here’s a quick rundown of the cast:

- Assassin: Glass-cannon, melee-DPS class with two swords and a shotgun side arm

- Battle Medic: Healing class equipped with a grenade launcher and capable of flight

- Enforcer: Support soldier class with a nice machine gun and grenade

- Gunslinger: Precision class with two handguns, the first precision the second auto

- Harrier: Support class complete with a laser rifle, laser boots, and a small heal

- Juggernaut: Tank class with a big shotgun, a big health pool, and the ability to deploy barriers

- Titan: Heavy DPS class with a rocket launcher and a electric flamethrower-style side arm

- Vanguard: Glass-cannon DPS class equipped with a Gatling gun and flight

- Wraith: DPS class mixing melee abilities, gunplay, and speed

On first look, there are a lot of classes that can play supporting roles (Battle Medic, Enforcer, Harrier, and Juggernaut); however, what most class-based arena shooters call support and what Lawbreakers calls support are different levels of violence.

In Lawbreakers, you help the team by being fast and killing regardless of who you’re playing as.

The Battle Medic, for example, has fire-and-forget heals, meaning you’re spending most of the game flying above everyone else and raining down grenades or picking off stragglers with her pistol. I do a lot of healing sure, but I also do a ton of damage. She’s an absolute joy to play and probably my favorite healing class in a video game ever.

The other supporting classes follow in a similar line, with the Enforcer and Harrier packing fairly high-DPS weapons despite offering team buffs. Juggernaut is the only one who really feels more like a tank, but he offsets that by being able to deploy shields that can stop enemies from scoring objectives or entering healing stations.

As someone who loves arena shooters but isn’t very good at them, I love that the supporting roles are just as viable and fun to play as the DPS ones.

The DPS ones, meanwhile, are absolutely insane. Aside from the lumbering Titan, movement is nonstop speed and action, with teleports, grapples, and a lady that’s half fighter jet. Everyone feels good to play as, especially the Vanguard and Assassin classes who have more erratic movements. The Vanguard really does feel like you’re flying an airplane complete with machine guns and cluster bombs, and the Assassin feels like a cross between Spider Man and Ryu friggen Hayabusa.

Every time I jump into another match of Lawbreakers, I’m always surprised at how good and fun the general movement is.

On the whole, the game is pretty balanced, with one or two ultimates being a little more powerful than they need to be. Still, given the wide disparity in health values, I very rarely find myself exploding with no reason behind it. There’s always that little chance I can exit a bad fight and grab more health.

I’d say the TTK is about perfect, or as perfect as a class-based shooter can be.

The game modes themselves offer another twist on the arena-shooter genre in that there is no Death Match or Team Death Match. Everything is objective based, which is something I really, really appreciate. Objectives breed more variety than simple run-and-gun, and I feel less bad about dying left and right when I’m helping guard a battery or cap a blitz ball.

Lawbreakers comes with five modes, two based off of King of the Hill, two off of Capture the Flag, and one off of Assault. The two King of the Hill type modes are standard, but the others act as an evolution of their predecessors. The two CTF modes involve holding a battery at your base to charge, meaning capping isn’t just about retrieving the battery—you have to defend it too. I’m not sure that’s an inspired change or not, but it does add a new dynamic (and a new level of tension) to a tried-and-true game mode.

Blitz Ball is the Assault-style mode, though it’s more of a sport than an assault. The ball has to be taken to the enemy base, but given how fast Lawbreakers is, it typically winds up shooting everywhere like a deranged game of soccer where everyone has a gun. When a Titan or Juggernaut grabs it, the mode slows down to a tense trudge ala football.

Suffice to say, it’s an absolute blast.

It should also be noted that while Lawbreakers is $30, it comes with a lot of content. There are nine characters, five game modes, and eight maps. There are also tons of unlockables, though they’re all found in loot ‘Staches that have to be found our purchased via real money. Thankfully, they only contain cosmetic items such as weapon skins and decals, so you don’t have to worry about any pay-to-win mechanics here.

While fun can be had in spades, Lawbreakers isn’t without its few quirks and problems. The first big one is that it wastes the player’s time. Time between matches can last up to a minute and a half, even when the lobby is full and everyone is ready. There’s no “Ready” system to speed things along. What’s worse is you can’t open ‘Stache boxes while waiting, so you’re stuck watching the clock tick down.

‘Staches open very, very slowly I might add. There’s no reason for it.

There’s also no way to pick what maps or modes you’ll be playing. Quick matches means it’s all random. I honestly don’t know why there isn’t a voting system with even two or three choices to pick from, as games like Halo have been doing that for ages. It’s one of the few times where Lawbreakers doesn’t feel modern at all.

Finally, the game does come with a very hefty skill ceiling. That’s less of a complaint and more of a fact of life, but there are a lot of little things to learn. The game doesn’t always do a great job of teaching those things, either. Some characters have side arms while others don’t, and none of that is effectively communicated.

I didn’t learn the Assassin had a shotgun until someone told me, for example. (Admittedly, I’ve never touched the tutorial area.)

That all being said, Lawbreakers is a fantastic arena shooter with a lot to love. It aims for fast, frantic, and fun, and it hits all three consistently. The classes are all fun to play, but the way it treats its supporting roles is really what I find shines the best. No one feels left out. Everyone feels viable. Little twists and turns abound, both in the gunplay and the game modes themselves, and while I have some small gripes, they’re just that: small.

I’ve been looking for a new arena shooter for what feels like a long time. I’ve finally found one.